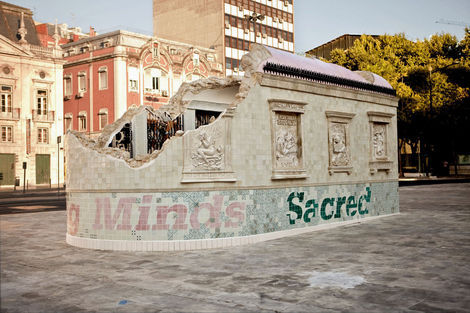

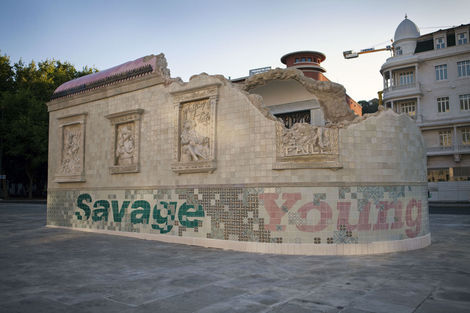

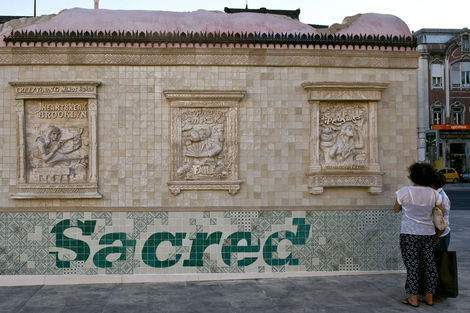

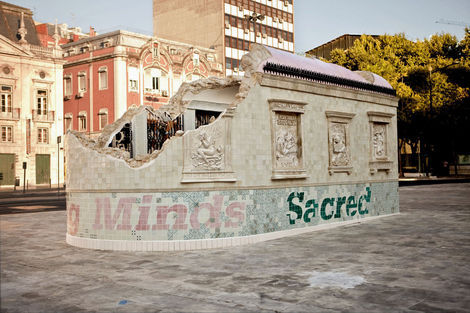

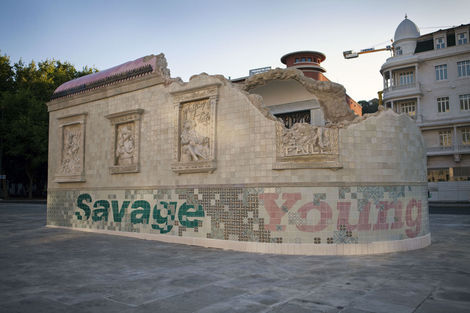

Faile Temple

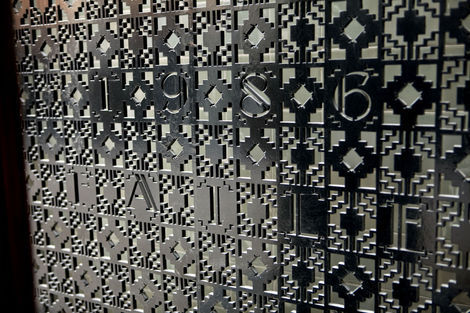

Materials: Ceramic, Marble, Bronze, Cast Iron, Steel, Limestone and Mosaic.

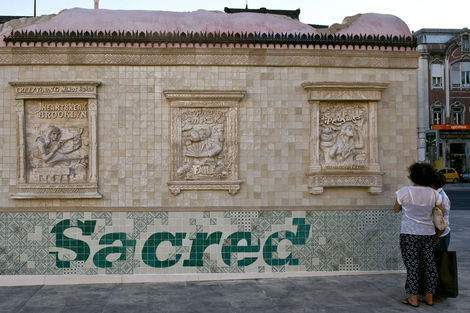

Dimensions: 16ft. Width / 30ft. Length / 14ft. Height

From 16 July to 15 August 2010, the Brooklyn-based artists Faile displayed “Temple,” a full-scale church in ruins in Praça dos Restauradores Square in Lisbon. The installation was made in conjunction with the Portugal Arte 10 Festival and will tour abroad. While Faile is well known by now for their arresting, advertising and Pop inflected prints and sculptures, “Temple” marks the duo’s migration from a more strictly visual medium into the realm of site specific environments. While its structure is the ruin, Temple should not be read as a memento or celebration of decadence but instead as one of collaboration and renewal.

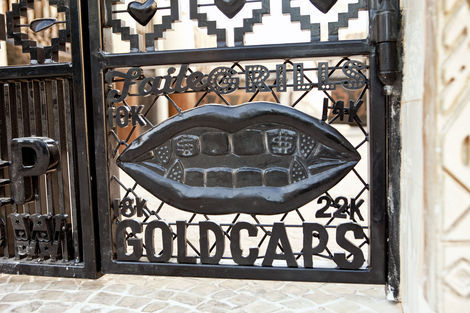

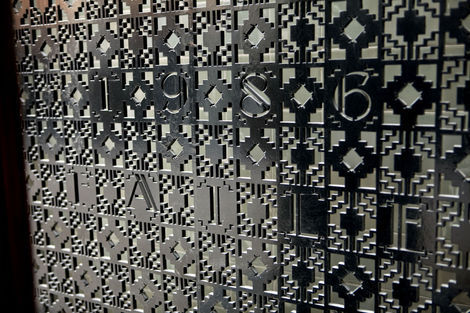

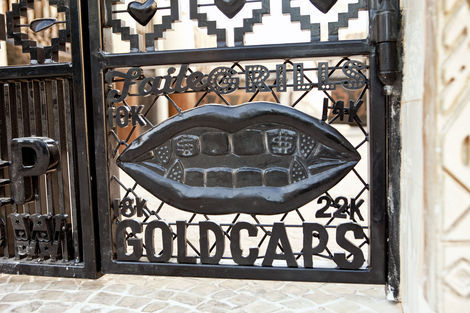

In retrospect, such a project seems inevitable: much of Faile’s recent work, from customized Buddhist prayer wheels to an American flag reworked with Pueblo-inspired linework, relies on re-imagining sacred objects on an increasingly grand scale. This year’s Deluxx Fluxx, a functional arcade bedecked in Faile’s trademark commercial iconography and vibrant palette, was a foray into immersive spectacle. Nevertheless, building a church from the ground up in an Iberian country is a symbolically freighted choice, and one that ups the ante considerably. Not only is sacred architecture deployed here as an artistic medium, it is forced to intermingle with the exotic and profane: Brooklyn-style window bars, new prayer wheels, and sculptural relief depicting Faile’s own idiosyncratic archive.

One might object that Faile’s use of religious objects devalues them by making them simply one more signifier in a visual system, divorced from their power and specificity. But the logic of Temple is neither the trivialization of pastiche nor the critical distancing of appropriation. Faile’s process is more aptly described as 3-D sampling, in which seemingly disparate pieces are brought together and reconstituted as something wholly other, but still animated by the energy, the spirit, of the original. In this case of course, the source material is 15th c. Florentine sculptor Luca Della Robia, not George Clinton. The result is a new site of public communion that recognizes religion as the social artifact that it is, but reminds us again of an underlying desire for unity that is often occluded by our urban edifices, be they cathedrals or skyscrapers.

In any case, it was from the shores of Portugal that Christendom first made its way across the oceans, from Goa to Benin and Bahia. Along the way, it syncretized fluidly with local traditions, resurfacing as Candomble and Santeria. Temple extends this tradition of dynamism and reinvention by returning Faile’s vertically-integrated vision of the church to the metropole, rooting its new permutations in the Portuguese cityscape. Like all ruins, Temple reminds us of the fragility of our most timeless institutions even as it lays the groundwork for its own sort of Renaissance.